This past weekend, with Lauren frantically attempting to set up her classroom before the kiddies arrive, I took the opportunity to sneak away to Denver to run in the Pikes Peak Ascent, far and away my favorite race of any kind.

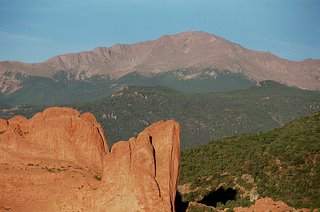

This past weekend, with Lauren frantically attempting to set up her classroom before the kiddies arrive, I took the opportunity to sneak away to Denver to run in the Pikes Peak Ascent, far and away my favorite race of any kind.Starting on a harmless patch of asphalt in the postcard-quaint town of Manitou Springs, Colorado, the Ascent takes runners 8,000 feet skyward before finishing atop the lunar-like summit of 14,115 foot Pikes Peak (on left). While the panoramic views awaiting the finishers are exceedingly beautiful (in fact, it was the view from the top of Pikes that inspired Katharine Lee Bates to write “America the Beautiful”), simply signing up for the race in no way guarantees you’ll ever get to enjoy them. The relentless climb (it averages 11% for the 13 miles), the increasingly disappearing oxygen (at 14,000 feet, there’s only 33% of the oxygen found at sea level) and the constant threat of unpredictable and dangerous weather conditions (rain and lighting is common; last year saw a freak blizzard) make just finishing this race an unparalleled challenge of both your body and mind.

When we woke Saturday morning, my buddy Max and I were greeted with rain for our entire drive from Denver to Manitou. As we approached the Springs, we could see the Peak shrouded in a mass of black clouds, which could only mean one thing: storms.

Storms can put a damper on any race; on Pikes, they can be deadly. Above tree-line (the point on a mountain where trees can no longer grow due to the decreased oxygen), there is no protection from the elements. If lighting should strike above 12,000 feet, YOU are the tallest thing in the vicinity. Even worse, temperatures routinely drop 30-50 degrees during a storm on the Peak. With any emergency clothes you may be carrying now soaked, there is no escape from the bitter cold, and hypothermia is a distinct possibility.

As best we could, we packed for the worst. We each carried over 25 ounces of water, plenty of food, and as many pieces of warm clothing as we could tie to our bodies. I even carried a cell phone in case of emergency, though it would probably be of little use in the places it was most likely to be needed. The added weight wasn’t going to make the climbing any easier, but it had to be done. And with that, we fought our way to the starting line, and waited for the gun to go off. And woudln't you know it, as we waiting nervously for our day to start, the rain suddenly stopped, and the sun emerged...

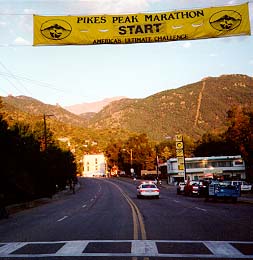

The funny thing about the Ascent is, the start does little to foretell the struggles to come. As 1,500 runners mill around the starting line, nervous habits as varied as the shoes on their feet, the scene is indistinguishable from any local 5K. The only thing that separates the start of this race from any other is this simple twist: at this race, one can stand at the starting line, and 13 miles in the distance, see the finish. All you have to do is look up.

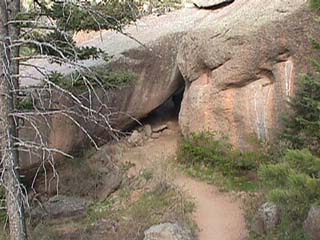

To the left is a picture of the famous Rock Arch, through which all runners pass about 2.5 miles into the Ascent. The narrow dirt path you see is the Barr Trail, which runs from the base of Mount Manitou, a smaller mountain adjacent to Pikes Peak, all the way to the summit of Pikes. You join up with the Barr Trail 1.2 miles into the race, and need never turn off it the rest of the way. If you look closely, you can see how the trail winds right between two eight-foot high rocks, with a third acting as a ceiling.

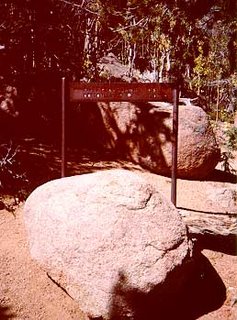

Five and a half miles and nearly 4,000 feet of climbing into the race, you come across this sign, which reads simply: Barr Camp .5M. It's a momentous sign for two reasons; one good, and one bad. While the sign indicates that you are only half a mile from Barr Camp, a hut that marks the half-way point of the race and is always jam packed with screaming spectators, it also serves as a reminder that the only "flat" portion of the race is over, and there's nothing but steep climbing and thin air ahead.

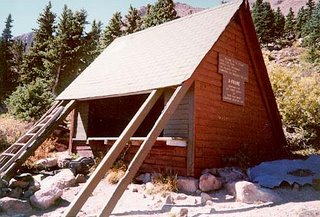

This is the A Frame. I'm not sure what exactly it's there for, but it's positioned 3 miles above Barr Camp, at roughly 11,500 feet. It's significant to the race for one reason: the tress you see behind the structure are the last you'll find on the mountain. Once you make the turn at the A Frame, you climb above tree-line, where only 3 miles of dirt and rock separate you from the finish line.

See, I told you. This sign, which reads "Pikes Peak 3M," is only a couple hundred yards from the A Frame. The change in the landscape is dramatic, and the lack of tree cover offers racers the first view of the Peak since the starting line. Never has anything looked so close, yet proved so far away.

The "Pikes Peak 2M" sign. As you can see, the once-smooth trail is not completely rock-strewn. The two mile sign means you've reached roughly 12,800 feet, and at this altititude, breathing is next to impossible. From this sign, you traverse across the face of the mountain all the way to the far edge, right where you see the sky meet the stone. This long, exposed climb has destroyed me twice: in 2002, my calves began to cramp with ever step, while in 2005, I went into a coughing fit each time I attempted to draw a deep breath. Good times.

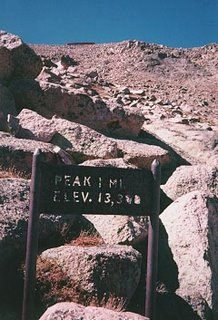

That says it all, doesn't it? Only one mile to go, yet it looks damn far away. And trust me, it is. There is still nearly 800 feet of climbing left, which over 1 mile, makes for a grade in excess of 16%. To be honest, though, the first half mile isn't that bad. It even has some flat portions, that is, until you hit...

....the 16 Golden Stairs. Named by Fred Barr, these are 32 switchback that take you the last half mile and 500 feet of vertical to the finish line. Each pair of switchbacks makes up a "stair." They are, undeniably, the most difficult stretch of any half or full marathon in this country. At 14,000 feet, your lungs are burning and your muscles failing. Each step, you're forced to lunge high onto another rock with legs starved for oxygen. The worst part is, you can hear the announcer calling out the finishers, but you can't SEE anything, as it's all taking place directly above you. Finally, when you think you can't go any futher, that you may have to crawl or stop completely, you make one final left hand turn, and you can see it...the finish.

This year, more than ever, crossing under that banner brought with it a feeling of satisfaction you can't imagine. Having missed four months of training, I had serious doubts whether I would ever see the summit. But as Max says, "one foot in front of the other will get you there." And, as usual, he was right. While my time was considerably slower than in years past, I have never ran a race of which I'm more proud, simply for the fact that as much as I wanted to throughout those last five miles, I never quit. And it's all because of her.

And here's the proof! That's me and Max proudly posing at 14,115 feet. As you can see, the storm clouds were just starting to roll in as I finished. That left me just enough time to get my medal, throw on some warm clothes, steal an inordinate amount of post-race M&Ms, and snap this photo. Then it was onto a van and down the mountain, where the oxygen was waiting.

And just think, next year, my truly badass sister Karen could be standing right between Max and I, celebrating her first Pikes Peak Ascent. If that doesn't get her to start training in December, nothing will!